An Introduction to Good Grief

Painting loss, gives new meaning to life

In reviewing the theme of some of my artworks over recent years, I realized a consistent thread appear between the subjects of my paintings, which is that I have spent a large majority of my time painting things that have died. Particularly, this theme emerged for me around 2021. In retrospect, I wonder whether this emergence was produced in part because the massive death-toll from the global pandemic acquainted all of us with the mortality of life in a way that normalized and leveled our collective experiences. In actuality though, it began when close friends and mentors started opening up their wounds, sharing stories of their loved ones who had passed away, then asking me to personally create a painting to memorialize them. These were no small tasks and I treated their requests with the utmost responsibility.

For the purposes of acknowledging a beginning of this series (although there were earlier iterations and smaller starts that allowed this theme to percolate for years preceding this moment, which I will expound upon later on), the first so-called “grief painting” I completed was for a law school classmate who lost her mom to cancer during our 2L year. I had met her mom just once in-person, but that singular time coupled with the stories my classmate shared with me about her mom were enough etch her personality and memory into my mind, unknowingly preserving it for the exact moment my classmate asked me to paint her mother’s portrait prior to our law school graduation.

Accepting the responsibility of this artistic endeavor carried with it a challenge I had not experienced in other artworks. The typical difficulties with portraiture are capturing the subject’s likeness, incorporating the appropriate colors and contrasts, deciding on composition, and the like—the usual, understandable artistic elements. But here, in addition to these expected challenges, I was faced with something new—something that even went beyond the pressure to preserve and protect the personal qualities of the subject. Rather than the physical challenges of painting, it was an emotional hardship faced by me, the painter, one in which I entered into the grief of the commissioner, my law school classmate, and mourned the loss of the subject, her mother, as I painted. Attuned to both sources—the living’s request for a painting and the dead’s desire for a memory—I, in the middle, as a medium had to listen intently to each, allowing my brushstrokes to be guided, my palette to be enlightened, and my vision to be directed by their input. This entire artistic process was a form of vicarious bereavement, pushing my already inherently empathic nature to a higher, more intensely feeling state, well-beyond compassion or sympathy, to the point that her loss was intertwined into my own.

Just a few months after completing this first grief painting, I received an urgent and upsetting message from another friend stating that her mother had just passed away and immediately, in seemingly her next breath, she asked if I would paint a portrait of her. Honored, and less hesitant than the first, I took on the same responsibility of the previous grief painting. However, there was a difference this time in that I never personally met the subject. Still, I had heard about her for years in the stories my friend shared about her mother. Upon seeing a photograph of her, I realized how much her countenance resembled my acquaintance. This grief painting was far more reactionary than the first. Once completed, it was like an offering, expressing my condolences to my friend in the same way people donate flowers at a funeral or show up with prepared meals in the weeks following a loved one’s death. But where flowers die and meals are digested, this painting I again hoped would preserve and protect the memory of my friend’s mother for many years to come.

In between these two seminal works, I created a third grief painting honoring the life of another deceased mother. A year or more prior to putting my brush to this particular canvas, I was inspired by a story a mentor of mine shared about her mother, who like my classmate’s mother, also died while my mentor was a law student. The story she shared went something like this: Following my mentor’s first court appearance, her mother sent her a dozen roses with a pair of underwear tucked inside the bouquet and a note that read, “Stay wild.” Shortly thereafter, her mother passed away. My heart broke when she shared this story and the way she told it—teary-eyed—I could tell she carried the grief of her mother closely. It makes sense to me now that upon completing my classmate’s portrait of her mother, I transitioned into creating a painting for my mentor, given their undeniable parallel loses. But having no context for what my mentor’s mother looked like the subject matter could not be a portrait in the traditional sense. The next best thing in my mind was a painting that captured this particular memory of her mother sending her the roses and underwear, so that is the painting I created. Somehow this grief painting, without depicting the appearance of a face, still preserved the memory of the individual it was designed to honor through the subject matter as a still life, rather than portraiture.

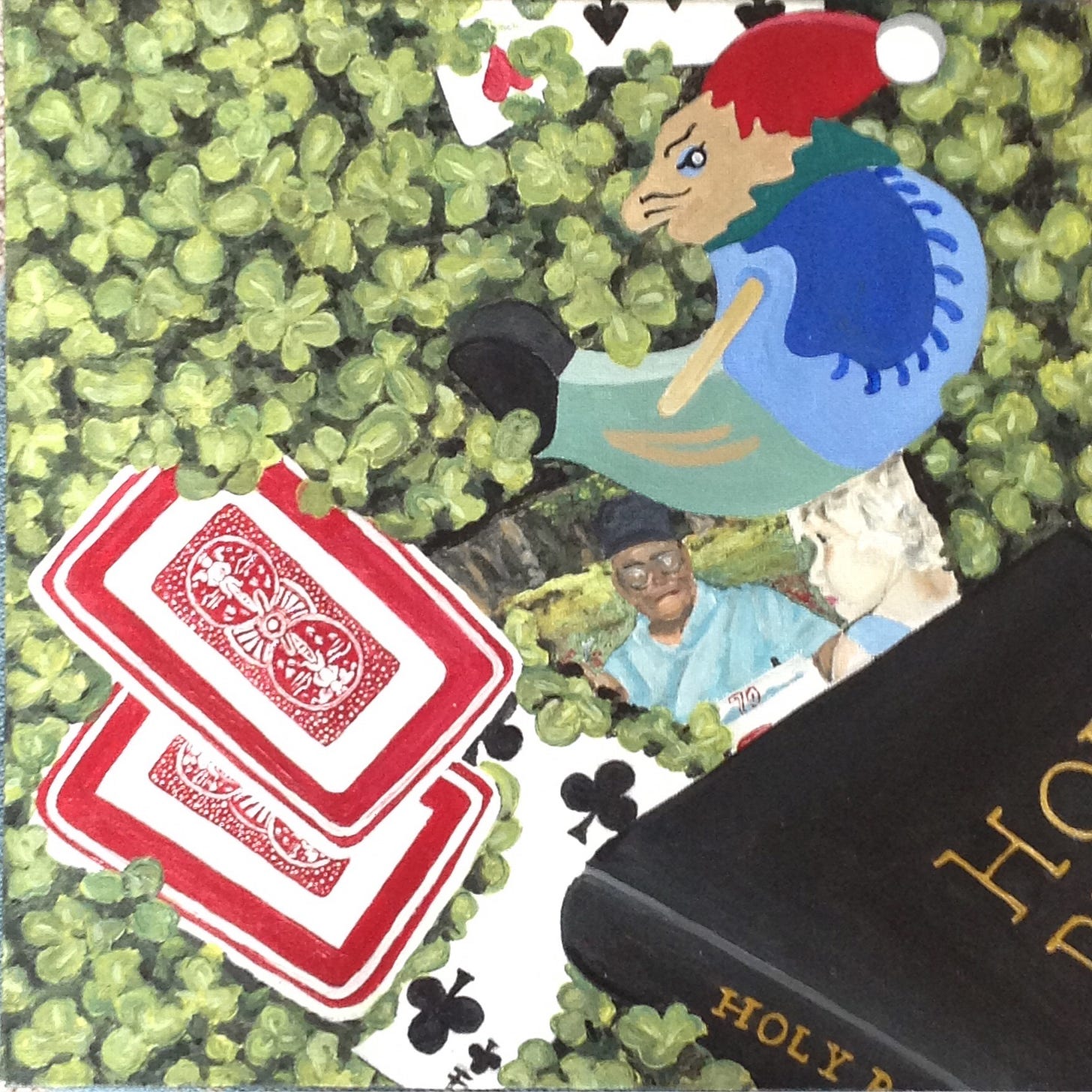

Along the line, I learned I was not alone as an artist depicting grief or loss through still life. Vincent Van Gogh painted “Still Life with Bible” shortly after his father, who was a minister, died. The painting displays an open Bible propped up on a table, against a a dark background with an unlit candle and a closed copy of Émile Zola's La joie de vivre nearby. This still life was Van Gogh’s version of a grief painting—memorializing his father not in portrait, but instead by representing himself, his father, and their relationship in the context of two books on a table. The way we remember people is not always in the way that they look, but by the things they did or the things they leave behind. Oddly, prior to discovering this Van Gogh piece, the first painting I did of my paternal grandfather following his death was also a still life with a Bible. I was seventeen-years-old when my Pap died, and an eighteen-year-old, soon-to-be high school graduate, when I completed this painting for a senior year art class. My Pap was not a minister by trade, but rather a man of deep faith. In addition to a Bible, I arranged a composition incorporating one of the handmade wooden toys my Pap created, playing cards, and an old photograph from his 70th Birthday party when I was just two-years-old, all laying in a bed of clover. In its entirely, each portion is symbolic and meaningful for the moments I spent with my Pap while he was here and how I hoped to remember him now that he wasn’t. For an adolescent, experiencing for the first time the loss of someone close to her, the fact that all I could muster was memory through still life not through portraiture, to me now exhibits this inability to come to terms with my Pap’s death.

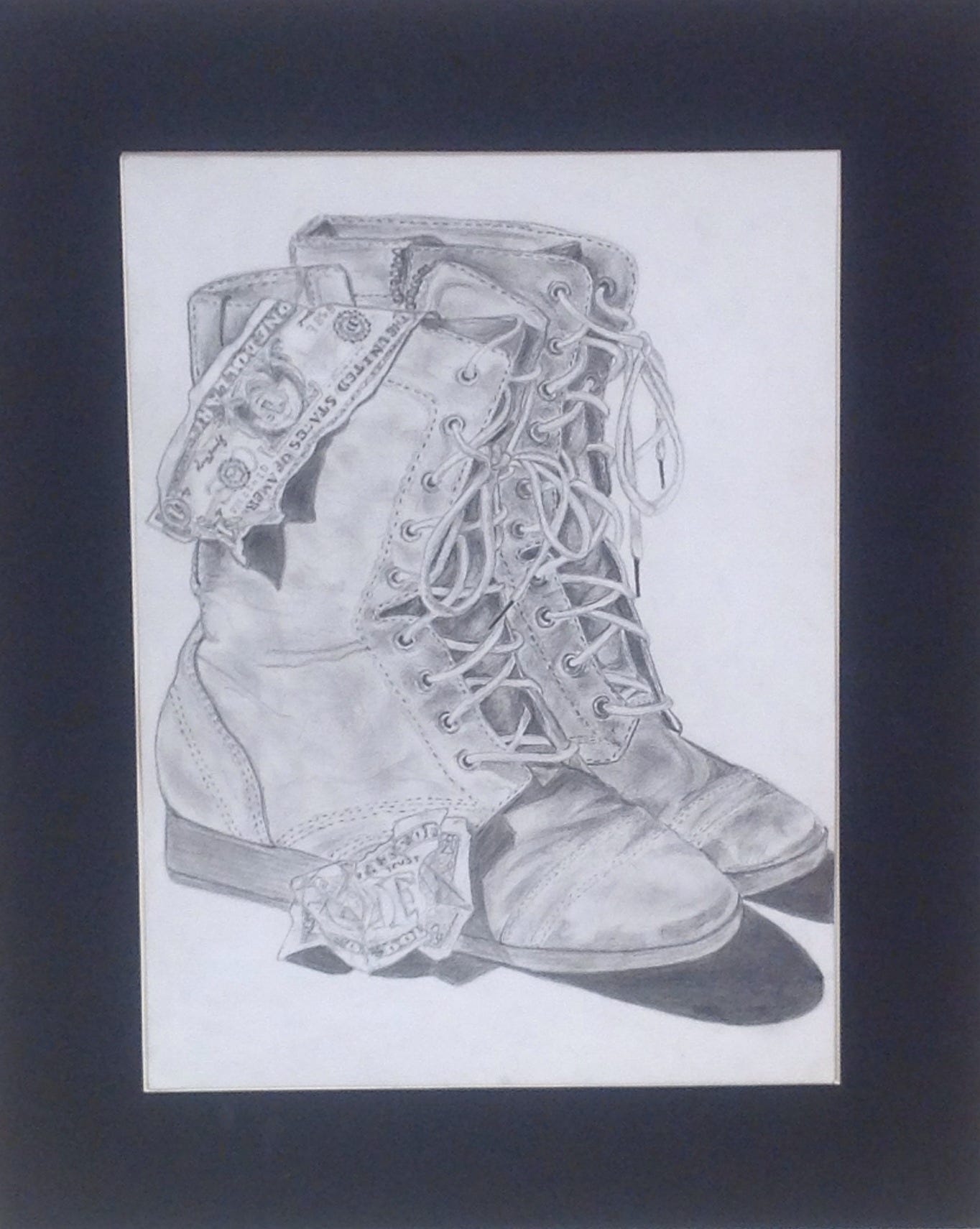

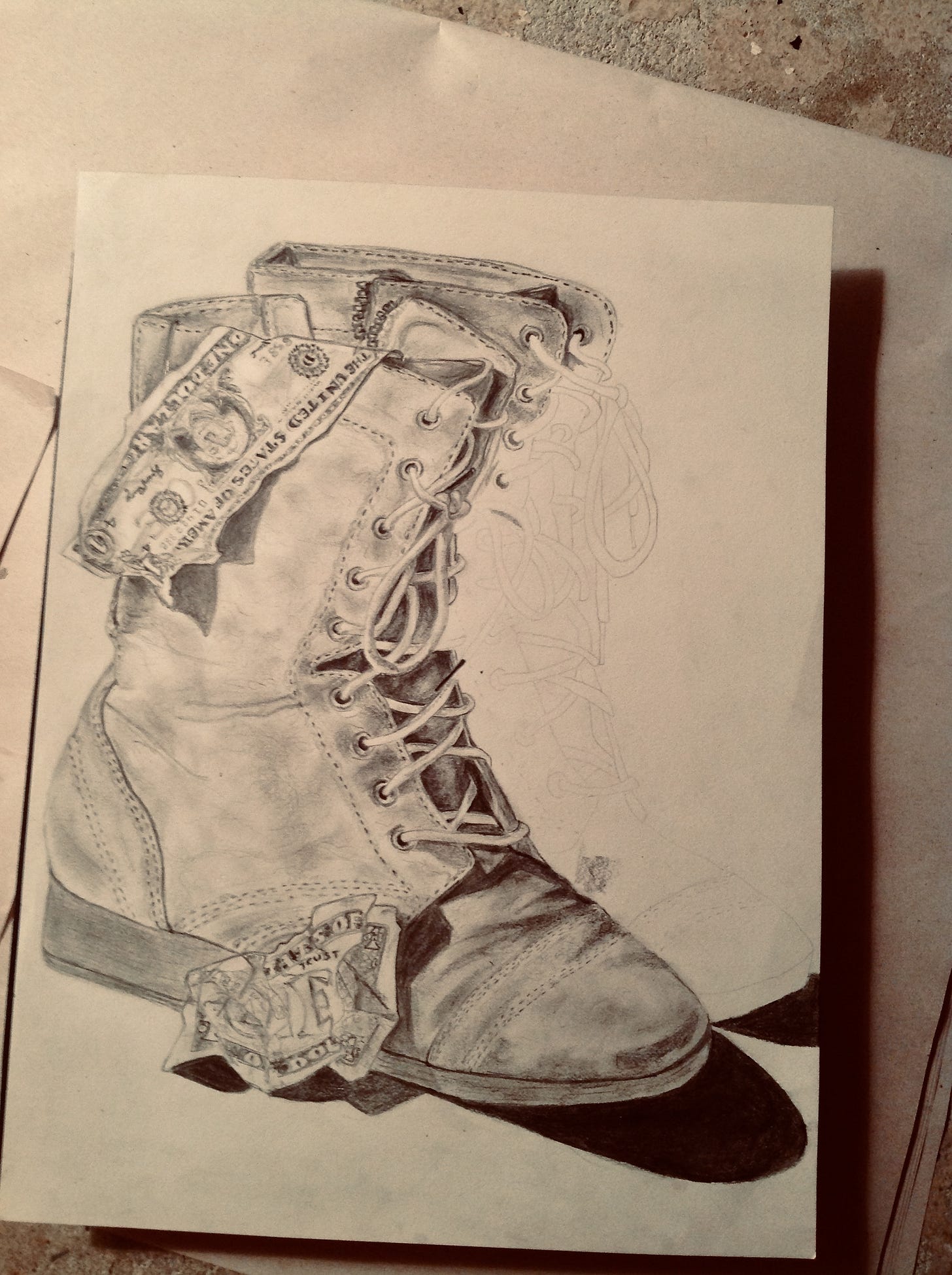

Prior to this painting, in response to the loss and deep emotion immediately following Pap’s death, I created a still life drawing of a pair of combat boots I had worn back then with crumpled up dollar bills. The drawing was a depiction of one of the phrases I heard my Pap say to emphasize his certainty, “Bet your boots.” I titled the drawing with that same phrase. I find it fascinating that even in my own grief at a far younger age than I am now, in response to loss, my reaction was to create. Turning pain into preservation, memory into creativity, death into art, seems to be a theme in much of my life and life’s work. Processing grief through still life is ironic only in name and practical in every other sense such that in those depicted objects the dead are still very much alive. It is as if in these objects there is ‘still life’ for the things we’ve lost. The fact that these objects are still here in the physical sense makes it seem like those that are dead are not gone entirely, like our loved ones are also still here in the physical sense, even if it is in pieces—and that somehow their life still exists, telling us that there is still life worth living.